History

a history of the women airforce service pilots

In early 1942, Nancy Harkness Love’s pilot skills caught the attention of Col. William Tunner. Love convinced Tunner that the idea of using experienced women pilots was a good one. Tunner appointed Love to his staff as executive of women pilots. Within a few months she recruited 30 experienced female pilots to join the newly created Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS). Twenty- eight pilots, “The Originals” as they were known, graduated training and Love became their commander.

In September 1942, the women pilots began flying at New Castle Army Air Field, Wilmington, Delaware. By June, 1943, Love was commanding four different squadrons of WAFS at Love Field in Texas, New Castle in Delaware, Romulus in Michigan and Long

Beach in California. Love hoped that women could serve alongside their male counterparts and eventually join the military as equals. She made no plans for a segregated unit nor expanding WAF duties.

When the Ferrying Command became the Air Transport Command, Lt. Gen. William Tunner became commander of the Ferrying Division. At that time, the division was ferrying from factory to user, 10,000 aircraft monthly, including over-seas deliveries (af.mil/about-us/biographies). He was faced with a severe shortage of pilots as he struggled to keep up with demand.

Tunner was scouring the country for skilled pilots and was amazed to discover that accomplished pilot Nancy Harkness Love was serving in an administrative capacity on his base. He wanted to know if there were other women who could fly. Within days, he met with Nancy and asked her to write a proposal for a women’s ferrying division. Within months, Love had become the director of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferry Squadron, or WAFS, with 28 experienced female pilots under her command. These female pilots gave Tunner the womanpower he needed to meet the growing demand for aircraft delivery.

Nancy Love

1914 - 1976

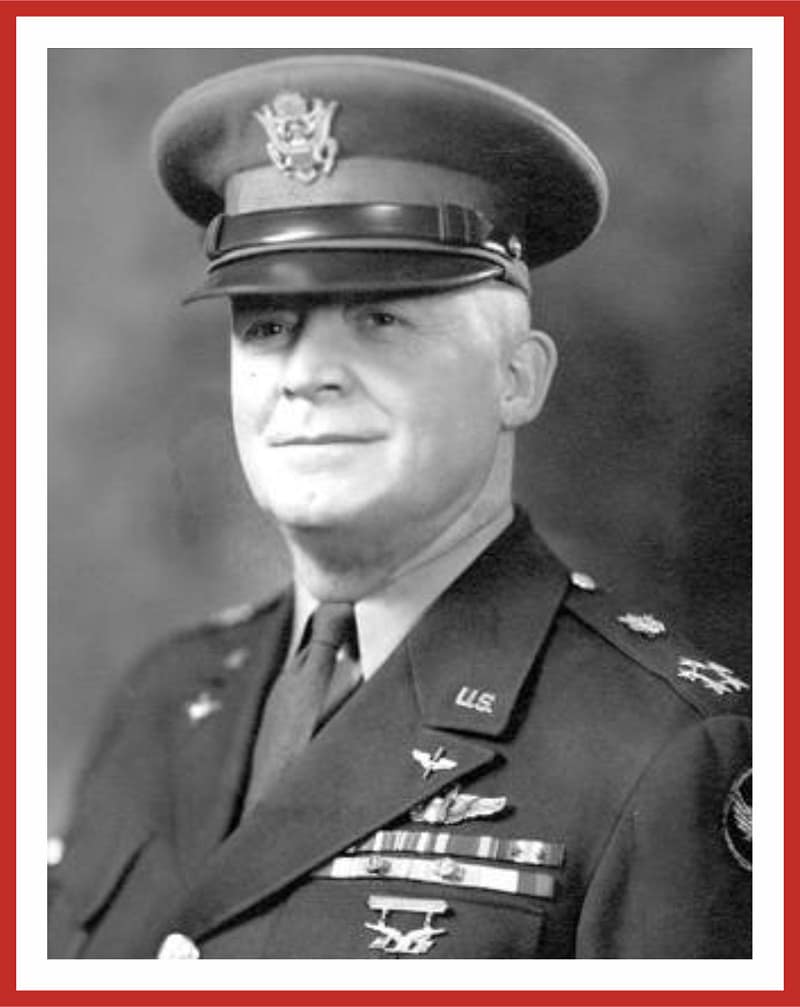

William H. Tunner

1906 - 1983

Jacqueline Cochran

1906 - 1980

Henry "Hap" Arnold

1886 - 1950

In 1941, as World War II began to escalate, Jacqueline Cochran recommended military aircraft flight training for women. Her idea was rejected. Unaware of Nancy Love and the position she had obtained under Col. William Tunner, Cochran took 25 women pilots to England to ferry airplanes in March of 1942. These ladies in the British Air Transport Auxiliary were affectionately referred to as “ATA-gals”.

When Cochran learned of the newly created WAFS under Love’s command, she returned from England and confronted Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, who had previously rejected her idea and demanded she be given the opportunity to form a segregated unit of women pilots who would not only ferry aircraft, but also other non-combat assignments such as towing gunnery targets and test flying newly repaired aircraft.

Arnold granted her request and formed the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) with Cochran as its commander.

In September of 1942, General Henry “Hap” Arnold finally approved of a program to train women pilots to fly military aircraft. He formed an experimental squadron of Air Transport Command, and 28 women pilots formed the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) under the leadership of Nancy Harkness Love.

Arnold expanded flying opportunities for female piltots when he sanctioned the creation of the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) headed by Jacqueline Cochran. In August 1943, the WAFS and WFTD merged to create the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Cochran was named director of the program and Love was head of the ferrying Division.

Twenty-eight women were accepted in the first phase. As more women were needed, the requirements were changed. The revised requirements were:

- American Citizenship

- 18-35 years old

- High school diploma

- Minimum height of 64 inches

- Pilot’s license

- Not less than 200 hours logged flying time

- Pass a physical from an Army flight surgeon

- And a personal interview with an authorized recruiting officer

Because this was a Civil Service program, the girls were required to pay their way to get to Sweetwater and if they washed out, they had to pay their way to get home. Room and board at the rate of $1.65 per day was deducted from their paycheck of $174.50 per month. They even had to pay for their uniforms.

The first class of 28 recruits assembled on November 16, 1942 at the Howard Hughes Municipal airport in Houston were introduced to the “Army Way”. The second class arrived in December of 1942, and another new group each month thereafter. By the time the third class has entered training, flying conditions at Houston were becoming increasingly overcrowded and dangerous. Plans to increase the number of students to 750, then 1,000 for 1944, made it essential to find more adequate facilities.

The decision to move the WASP to Avenger Field in Sweetwater, TX was made. It was the only all female WASP base, and all flight training from primary to advanced was conducted there, or at auxiliary fields in the immediate area. Eighteen classes graduated the WASP Program.

The objective of the program was to see if women could serve as military pilots to release male pilots for combat flying and to decrease the Air Force’s total demand on the manpower pool. The program was under the Civil Service Commission with civilian trainees. There were 25,000 women who applied, but only 3,000 had their pilot’s license. Of these, 1,830 women were accepted after they met the criteria and passed a physical. In less than 2 years under Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Love’s supervision, 1,102 WASP flew over 60 million miles in every type aircraft in the Army Air Corps arsenal.

Ground school included classes in Meteorology, Navigation, Morse Code, Parachute Packing, Mechanics, and 50 hours in a Link Trainer. Daily physical fitness was conducted to improve upper body strength.

After each phase of flight training, the women had to pass a check ride with an army pilot. If they passed, they went on to the next phase. If they didn’t pass, they washed out and went home.

When trainees graduated, they were assigned to over 120 duty bases all over the United States. Over 300 of the women ferried airplanes from aircraft factories to areas of need. Some were assigned to Lubbock, TX, to the Glider Training Base. Many of the women became tow targets pilots for gunnery practice. The women would tow targets 1,000 feet behind their airplanes for men with live ammunition to shoot at them. Other graduates were sent for more training to learn to fly B-17s and B-24s.

Before the program ended, the WASP had flown 60 million miles in 78 different types of airplanes including the fastest pursuit planes and the heaviest bombers.

Thirty-eight were killed in service. The military did not pay for services or transportation. Their fellow WASP would take up a collection among friends to send them home on the train with an escort.

Because the war was winding down and men were returning home, the WASP were deactivated in December 1944. At the last graduation ceremony on December 7, Gen. Hap Arnold told the newly trained WASP, “you and 900 of your sisters have shown that you can fly wingtip to wingtip with your brothers.”